original posting date lost

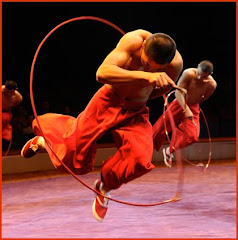

Most of my old VHS tapes I could easily toss. Funny how most of us, eager with new VCR machines 20 years ago, taped so many shows that we now have little desire to watch. Looking through mine, I came across the 1995 A&E documentary, not recalling how I had reacted to it when it first was shown. And so, back into my VCR it went, in total black and white since my once great Magnavox now turns every hue into black or white -- a new gizmo is on the way. Such wonderful footage came parading across the screen.

Then, I started taking notes, wondering, did it really happen that way? Was there a Sells-Floto Circus in 1900? Did Lilian Leitzel really fall to her death in 1928? (no.) Along the way, I think I spotted a very young Henry Ringling North sporting a snazzy hat, standing with some big shots near a Ringling ticket wagon. And somebody quoted Karl Wallenda as stating, "Life is always on the wire; the rest is waiting." Fabulous quote if he really said it.

And then I learned about Irvin Feld having this great idea to "save" the Ringling circus by taking it indoors, and getting John Ringling North to let him "manage" it in 1957, and moving it into the arenas. And it all came back: this peculiar revision of big top history came from the lips of interviewee LaVahn G. Hoh, who teaches "the country’s only accredited college level course on the circus in America" at the University of Virgina. And with such passion he spoke; perhaps Mr. Hoh was sincerely misinformed, or maybe a Feld operative of sorts. He was one of at least three "historiansinterviewed for the project, the other two being Tom Ogden and Dominique Jando. The mind reels, if you will allow me.

Errors small and great continued apace. Cirque du Soleil did not take American in 1984; it first took Los Angeles in 1987.

When you are matching quick simplistic sound bites with the footage that moves you, you end up fostering leaps in misinformation from one period in time to another, often skipping critical developments in between. Thus, does Jack Perkins tell us about John Ringling "running" the circus when, in fact, he shared authority with his brothers (many troupers regarded "King Otto" as the most powerful partner); And thus does Perkins give John Ringling North credit for a few years of great new ideas and acts in the 1940s, but virtually no credit for the 1950s. We can almost see the stage being set to favor the circus savior that, according to myth, would invariably enter the picture.

Con Colleano alone executed the forward somersault? I once held this error, later learning that others in fact have also turned the forward.

I had to wonder if the three "historians" who contributed to the piece were asked to check the script for errors.

Circus history, let's face it, has little textual meaning or value in these TV things other than to flesh out the seductive moving images on the screen. The average spectator evidently cares little about what really happened or who made it happen, just as long as the exotic world is brought to life.

And that's why the Art Concellos, the Irving J. Polacks and the Louis Sterns of the world, who made such critical contributions, end up as invisible as yesterday's ticket stubs lost among circles in the dirt.

Blame these glossy treatments Why we get so simple-minded, barely superficial overviews of the history of our American circus. And why I find myself once again, despite not being a fan of his at all, wishing that Ken Burns would dig his scholarly chops into the subject and give us the 30 hour treatment. I'd love to see what he and his colleagues see. One thing is certain, there is so much more to see and understand about a very complex and fascinating story than what usually trickles down on TV's occasional flirtation with old film footage of one of the world's greaest entertainment chapters, the old American circus.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment